What Exactly Is a Gemstone?

Gemstones don’t just appear in the ground – they’re the end result of extreme heat, pressure, slow cooling, chemical reactions, and a lot of time. Here’s a clear look at how gems are formed, from deep inside the Earth to right near the surface.

A gemstone is usually a mineral (or sometimes non-crystalline material like amber or opal) that is:

-

Naturally occurring

-

Hard enough to survive wear

-

Chemically stable in normal conditions

-

Transparent or translucent (most of the time)

-

Attractive in colour, brilliance, or pattern

All gems are crystals or crystal-like structures at heart, shaped by the conditions in which they grow.

The Key Ingredients for Gem Formation

Almost all gemstones need some combination of:

-

Chemical building blocks

Elements like carbon (C), aluminum (Al), silicon (Si), beryllium (Be), chromium (Cr), iron (Fe), and trace metals are the “alphabet” of gem chemistry. -

Temperature and pressure

-

High pressure deep in the Earth helps form gems like diamond.

-

High temperature can melt rock, creating magmas and fluids where crystals grow.

-

-

Time

Crystals need time to grow. Large, flawless crystals can take millions of years under stable conditions. -

Fluids

Hot, mineral-rich water moves through cracks in rock, dissolving elements and depositing them as gem crystals when conditions change.

Different combinations of these factors create different gem-forming environments.

1. Deep in the Mantle: Diamonds

Diamonds are a classic example of a gem formed deep within the Earth.

-

Starting material: Pure carbon

-

Conditions:

-

Depths of about 140–200 km in the mantle

-

Temperatures of roughly 900–1,300 °C

-

Enormous pressures (45–60 kilobars or more)

-

Under these conditions, carbon atoms are forced into a tight, three-dimensional lattice, forming diamond.

The diamonds don’t stay down there forever. They are brought toward the surface by explosive volcanic eruptions, traveling in pipe-shaped bodies of rock called kimberlites or lamproites. Once erosion wears away the surrounding rock, diamonds can end up concentrated in river gravels and coastal sands (called alluvial deposits).

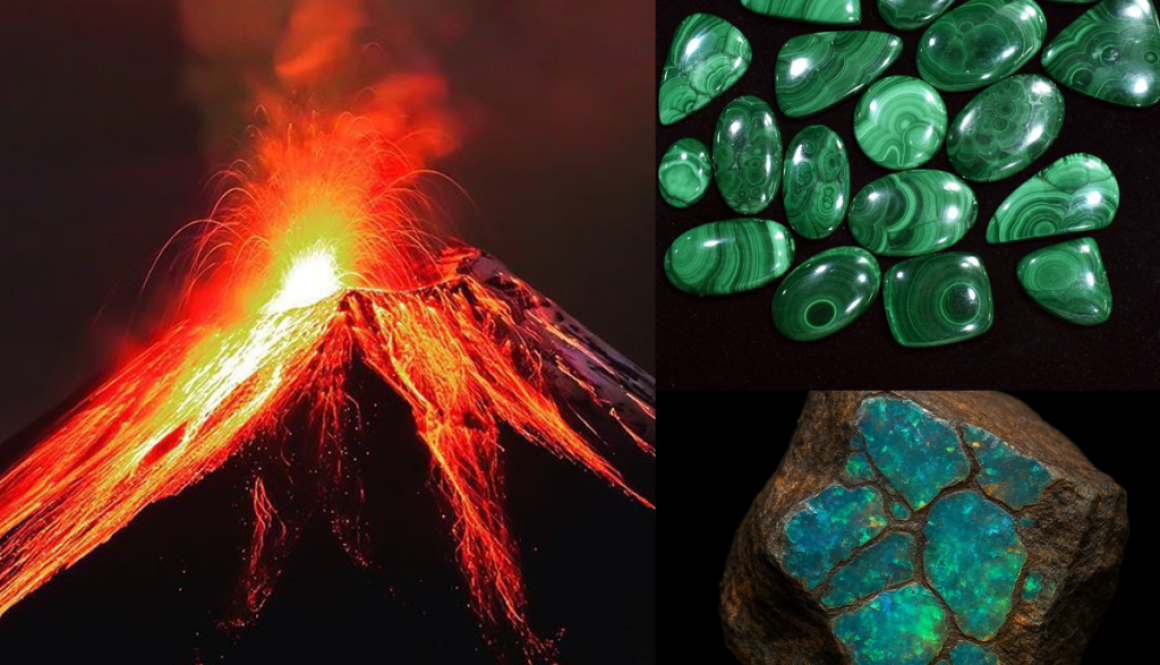

2. Magma and Pegmatites: Beryl, Tourmaline & More

When rock melts into magma, it can cool and crystallize into igneous rocks. As this magma cools:

-

Common minerals (like quartz and feldspar) crystallize first.

-

Rare elements (like lithium, beryllium, boron) get concentrated in the leftover, water-rich melt.

-

This leftover melt can form pegmatites – extremely coarse-grained igneous rocks with giant crystals.

Pegmatites are treasure chests for gemstones. They can host:

-

Beryl (emerald, aquamarine, morganite, heliodor)

-

Tourmaline

-

Topaz

-

Spodumene (including kunzite)

Because pegmatites cool slowly and are rich in fluids, crystals have space and time to grow large and well-formed.

3. Metamorphic Rocks: Rubies, Sapphires, and Garnets

Metamorphism happens when existing rocks are changed by heat and pressure without fully melting.

When rocks containing aluminum, silica, and other elements are squeezed and heated in mountain-building zones, new minerals grow:

-

Corundum (aluminum oxide) forms in aluminum-rich rocks.

-

With chromium → ruby (red corundum)

-

With iron and titanium → blue sapphire

-

Other trace elements → pink, yellow, green sapphires

-

-

Garnets (a group of minerals) form in many metamorphic rocks, often during regional metamorphism (large-scale rock transformation).

Metamorphic gems often occur in:

-

Marbles (recrystallized limestone), where rubies and sapphires can grow

-

Schists and gneisses, where garnet, kyanite, and other gem minerals can form

4. Hydrothermal Veins: Emeralds and Quartz Varieties

Hydrothermal simply means “hot water.” Deep in the crust, water heated by magma:

-

Flows through fractures and cavities in rock

-

Dissolves metals and silica from surrounding rocks

-

Deposits them as minerals when it cools or reacts with different rocks

This process forms veins filled with crystals.

Common hydrothermal gemstones include:

-

Emerald – a green variety of beryl coloured by chromium or vanadium, often in veins cutting through black shales or limestones

-

Quartz and varieties like:

-

Amethyst (purple)

-

Citrine (yellow)

-

Smoky quartz

-

-

Fluorite

-

Topaz (sometimes)

These gems grow from solutions, often in open spaces like cavities and vugs, leading to beautifully shaped crystals.

5. Sedimentary and Low-Temperature Gems: Opal, Turquoise & Others

Not all gems need extreme conditions. Some form at or near the Earth’s surface in sedimentary environments, where rocks are broken down and reformed.

Opal

Opal is not a crystalline mineral but a hydrated form of silica:

-

Silica-rich water seeps into cracks and cavities in rocks.

-

When the water evaporates, it leaves behind countless microscopic spheres of silica.

-

If the spheres are uniform and neatly packed, they diffract light, producing play-of-colour – this is precious opal.

Opal often forms in volcanic ash layers, sandstones, or ironstone.

Turquoise

Turquoise forms when:

-

Copper-rich waters react with aluminum and phosphate minerals

-

This happens in the weathered zones of copper deposits, often in dry, arid climates

The result is a blue to green, opaque gem filling cracks and veins or forming nodules.

Other sedimentary-related gems

-

Malachite and azurite – copper carbonates, forming in oxidized copper deposits

-

Zircon and peridot can be transported and concentrated in river and beach sands as placer deposits because they are dense and resistant to weathering.

6. Secondary Deposits: Nature’s Sorting System

Once gems form, they don’t necessarily stay where they started. Weathering and erosion break down rocks and free the crystals:

-

Rivers transport these loose gems.

-

Dense, hard minerals like diamonds, sapphires, spinels, garnets, and gold settle in bends of rivers, gravel bars, or along beaches.

-

These are alluvial or placer deposits, which are often easier to mine than hard rock.

This is why some gem fields are in riverbeds and ancient stream channels rather than in solid rock.

Why Gems Have Different Colours

Colour in gemstones mostly comes from:

-

Trace elements

Tiny amounts of certain metals substitute into the crystal:-

Chromium → red (ruby), green (emerald)

-

Iron and titanium → blue (sapphire)

-

Manganese → pinks and reds in some gems

-

-

Crystal defects and radiation

Imperfections or exposure to natural radiation can create colour centers, especially in gems like smoky quartz or some topaz. -

Physical structure

In opal, colour comes not from chemistry but from the size and spacing of silica spheres that diffract light.

Natural vs. Synthetic Gems

Humans have learned to imitate nature’s conditions in labs:

-

Synthetic gems (like lab-grown diamond, ruby, sapphire, emerald) have the same chemical composition and crystal structure as natural ones but form much more quickly using high pressure, high temperature (HPHT) or chemical vapor deposition (CVD) and other methods.

-

They show that gem formation is just chemistry plus physics – but stretched over different timescales.

Natural gemstones, however, carry the history of Earth inside them: inclusions, growth lines, and subtle variations that reveal where and how they formed.

In Short

Gems are formed when:

-

The right elements are present

-

Under the right conditions of temperature, pressure, and fluids

-

For long enough for crystals to grow

Whether it’s carbon deep in the mantle becoming diamond, aluminum-rich rocks transforming into ruby and sapphire, or silica-rich waters leaving behind opal, every gemstone is a tiny record of the geological forces that shaped our planet.

If you’d like, I can now:

-

Turn this into a shorter, kid-friendly version

-

Expand a specific section (like diamonds or opals) into its own detailed article

-

Add simple diagrams you could sketch to explain these processes visually